12/01/2021 - Results and learnings PfR’s COVID-19 response

For many countries COVID-19 has affected achievements across the wider development spectrum, with communities suffering secondary effects that stretch to income, food security, access to water, health and hygiene facilities, and gender equality. Vulnerable groups are even more disadvantaged. Consequently, response to the pandemic should be holistic to encompass these different fields, should be local to respond to the specific needs of affected communities, and should be flexible enough to adapt to specific containment actions of governments.

PfR’s response to the COVID-19 crisis I In the first weeks and months of the pandemic, the most acute needs in the PfR programme implementation areas became clear. With identified shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) and handwashing stations, an absence of information campaigns, and growing food insecurity, PfR planned to respond to the pandemic crisis. In May 2020, PfR received approval from the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs to shift a total of € 1.397.199 from the ongoing Dialogue and Dissent programme towards COVID-19 response.

The planned programme was based on observed immediate needs, centred towards four outlined objectives:

- The most vulnerable people in targeted communities are assisted to cover their basic food, water, hygiene, protection and mental needs.

- PfR partner CSO’s have the capacity to carry out COVID-19 prevention and response activities in close coordination with other (national) stakeholders.

- Targeted communities have improved livelihoods and imroved response preparedness capacity.

- PfR and its partner provide a bridging function between response, recovery, preparedness and improved resilience.

Because of built up partnerships, strengthened capacities and good relations and proximity to target communities and local government, PfR was able to reach out to people most affected. Trained staff and volunteers, earlier involved in community risk assessments, could use their skills to get a good understanding of people’s most urgent needs. Vulnerable groups, often already identified during the PfR programme, were targetted. Besides new vulnerable groups were identified, like migrants (e.g. migrants living on the Maldives who couldn’t return home), people who lost their jobs due to transport restrictions, and people who lost their source of income due to the lock down.

Multiple-risks I Additional challenges arose in some countries were natural hazards took place simultaneously. How to evacuate people in times of social distance? How to ensure access to water during the dry season, and during times of heat waves? Those additional challenges required attention as well, as they posed additional threats to already vulnerable communities. In India for example, COVID-19 awareness campaigns were linked to disaster preparedness messages, which led to enhanced public awareness and behavioral change in 6 States where outreach messages combined COVID-19 messages with do’s and don’ts on heatwaves and flooding. People reached benefited from the twin message on safeguards for COVID-19 and the associated messages on the need to preserve water and to harvest rainwater. This has helped to strengthen resilience of poor communities to COVID-19 and to heat and water-related disasters.

Programme results I It can be concluded that the interventions have been very timely and effective. The capacity strengthening on integrated risk management, risk analysis, community risk reduction planning, the disaster risk reduction committees earlier established and trained, and linkages established with local authorities helped to quickly coordinate and engage in intensive awareness raising campaigns, and the identification of the most vulnerable communities. This made the required support easier, quicker and more effective. In Mali, coalitions formed and capacitated by PfR, played an important role in the COVID-19 programme. Local partners organisations in all countries were a great asset to set up awareness campaigns to reach even the remotest communities, among others in Haiti where young people were trained and played a vital role in information sharing in their respective communities. The large presence of PfR partners and their volunteers, and the strong acceptance at the level of communities, contributed positively to the programme; local communities already knew and trusted the people now involved in the awareness campaign and COVID-19 response.

.png)

Around the world people adapt to COVID-19. These videos show how different people around the world are impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and how they try to deal with this new reality.

During the pandemic, PfR made this Podcast: listen to the voices of ordinary people in various communities around the world. The lockdown in many places has led to increasing vulnerabilities to people who are already living in difficult situations. These few voices speak for millions.

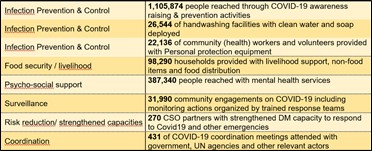

The below table shows how many people/ households have been reached:

Awareness campaigns: Communication and awareness raising on the new COVID-19 virus, and on prevention measures was provided. Information was shared on social distancing, face mask use and handwashing. This was done in various ways, for example by printing posters, leaflets, using radio airtime, using theatre/ music groups and megaphones. Local partners and their volunteers played a key role in awareness raising on do’s and don’ts during a pandemic. Local volunteers know their own community members best; therefore, they were able to bring the message across, using language which is familiar and well understood locally. In the Philippines, all networks and partners recognized the crucial importance of the IEC efforts, and were extremely resourceful and creative in activating this area of work through physical media, radio, TV and online platforms. The scope of the outreach was a result of PfR's investment in enhancing cooperation between various actors through local networks. In Indonesia, Red Cross volunteers distributed cloth masks; the mask itself could be seen as a property which the volunteers could use to start a conversation with their peer community members to share key messages related to COVID-19. Communication was crucial to inform people on this new virus but also to avoid stigmatization, support people with symptoms to search medical assistance and to combat fake information.

Preventive measures: In many locations handwashing stations were installed. To make sure people would use them they were launched during special organized events, and they were made attractive e.g. through paintings. The provision of hand wash stations with potable water and soap was supported with health and hygiene education which is essential to protecting human health during all infectious disease outbreaks. Kitchen sets were distributed in order for people to be able to cook themselves instead of going to the large communal kitchens. This was important to create social distance. Water storage at household level had similar effects, especially in dryer areas, as people did not have to go to community water points (India).

Support to government: screening centres were set up at markets and border posts to avoid spreading. In Uganda, the Red Cross was given a special mandate to substantiate on government’s efforts to conduct screening of people and vehicles on major borders. Ambulance services were supported in several locations.

Protection materials: Personal protective equipment was distributed to staff involved in COVID-19 response. Protection materials like masks, as well as infection prevention and control equipment, like hygiene kits, cleaning materials, soap were distributed at large scale.

Livelihood support: was crucial for people who were without any safety net. Support was provided through food distributions, cash vouchers or cash, food kitchens, and by providing farm utensils and seeds (especially to people also affected by locust in some countries in the Horn of Africa). Making face masks provided livelihood activities: Among other in Indonesia and India local women groups and volunteers took the opportunity to make masks. In South Sudan, where youth employment is very high, 10,075 masks were made through organizing and training young producers, who gained employment and income.

Supporting volunteers and local staff: Important were the efforts of local staff and volunteers who have been trained on how to deal with COVID-19 and to assist the communities. Supporting local staff members and volunteers was done in various ways e.g. with protection gear, heatlth insurance, and communication support to enable them to talk to colleagues. Additional staff was recruited and per diems paid for volunteers to scale up surveillance, house visits and risk assessments. Psycho-social support was often an important topic, both for the sanity of the local staff members as well as for the local population.

Insights and learnings I After being a year in a global pandemic, organisations worldwide -including PfR- have gained many new learnings regarding the way to look at disasters and health risks:

- Health should be an integral part of countries national disaster risk reduction policies and plans; plans should incorporate health as well, e.g. how to deal with a pandemic like COVID-19.

- Besides, in disaster management plans, multiple hazards should be taken into consideration, especially those who can take place simultaneously; more emphasis is required on multi-risk emergencies instead of sector plans.

- Working in multi-stakeholder partnerships is beneficial to deal with such a large crisis as a pandemic; as we see in the present crisis health is not the only concern. The crisis causes many other problems that require attention, e.g. lack of income, shortage of food and water.

- Psycho-social support has been able to enter the humanitarian agenda during this pandemic. Psycho-social support modules needs to be deepened and local partenrs need better training in order to be well prepared for such support.

- There is a need to better understand the relations between the environment, disaster & climate risk, and health. In COVID-19 response, due attention should be paid to Green Recovery. In Bihar, India, the example of providing food security support through paying man-days labour to revive eco-systems, showed this is well possible – even in the early response to the crisis.

- The recognition and value of data was obvious, and enabled organisations to better respond to the situation (e.g. in the Philippines).

- Localization is key for the success in this COVID-19 response. Many local volunteers were able to assist, which is interesting in the light of the localization agenda/ Grand Bargain commitments. The capacity strengthening delivered by PfR to national and local partners has paid off. For example, the improved capacity for policy dialogue: PfR partners in Maumere, Indonesia facilitated the making of COVID-19 policies and actions in the region. In Haiti, the involvement of youth volunteers increased considerably in COVID-response. The coalitions in Mali, formed and supported by PfR, took an active role in especially COVID awareness campaigns.

- During the present crisis, early action protocols could be practiced in reality, also linked to cash interventions. In Uganda, the unconditional Cash Voucher Assistance was very much appreciated by the beneficiaries because of its flexibility in terms of meeting basic human requirements.

Find the full report of PfR's COVID-19 response here